Samuel's nose twitched, nostrils flaring like sails. "Bread!" The smell painted itself onto the boy.

"No way. What bread?" That was Iliahi.

"You got stuck nose, and no imagination, Ahi," Samuel teased. Still dripping with ocean, Iliahi gave Samuel a raspberry then blew the snot from his nose. "Yeah, well maybe I got stuck nose, but you ... you have too much imagination."

"There's never enough imagination. Imagination makes dreams possible." Squinting at the diver with squirming he'e making undulating shapes of the old flour sack Samuel spread his arms wide, and wider to punctuate.

Iliahi Clark raised the bag with his morning's catch and his goggles with his left hand, signing the cross with his right-hand. "Imagination and dreams. Cannot eat." He lifted the octopus to his lips smacked appreciatively, and shoved the bag into Samuel's belly.

"Shoulda kept that to myself," Samuel said, but smiled to think of his grandmother who imagined impossibles all the time.

"I gotta go. School," Iliahi was Samuel's age, and it was a school day for him. Samuel and his twin sisters were home-schoolers. The beach was school. The lanky diver boy was a head taller than Samuel and glowed like sunrise with skin the color of iliahi. Sandalwood. He shook a head of blond hair that stuck to his shoulders. Every morning, before sunrise the boys met at the same spot along the Windward shore. To be on the sandy shore and cool ocean while still dark took a lot of trust on their parents' part. Well, Iliahi was hanai, adopted in the traditional meaning, and raised by his aunty along with a younger brother and a cousin. And Iliahi knew Aunty cast her mana, her protection over her boy, and nobody would mess with that woman, or her people.

"Lata, Sam. Going to the market?"

"Yeah. I'll be there."

"Me too, if I'm not pau with the yard work before you pau ... save me a slice of whatever your dad whipped up." Iliahi knew the bread would be crunchy on the outside and smooth like all heck on the inside. His mouth watered as he reached to slap Samuel on the head. Samuel dodged his friend's outstretched palm, and caught his wrist. Kids didn't know to keep their hands off the po'o.

"The head got important business to do, Samuel," his grandmother's voice clear as ocean. And this morning Samuel had a strange new feeling ... a kind of floating away. Then he felt his thoughts return to the moment. This moment. Have to remember to tell Ahi not to do that. Next time.

Samuel stalled his friend's exit, "You drying the he'e, even steven." Samuel used his hands to mimick a scale. He and his family loved the chewy tentacles eaten like long-lasting candy."

"Nope, Aunty making squid luau, with he'e but." That was even better thought Samuel.

"Imagina-tion! See you."

The sky was already lightening. One of Samuel's favorite times of the day. Like caterpillar breaking out of the cocoons. Was new. A new day, a new way. Drawing in a deep breath he smelled the bread again.

"Prickly and sweet." Samuel said to himself. The dog gave Samuel a half-interested sniff. He heard the comment, but focused on the breeze coming off shore. The tide was low and the smell of rotting seaweed and small crabs trapped in the mash of green and purple enticed the low-riding, shiny black mutt.

A poi dog sorta, Grog was mixed breed with one white ear, and one black which was notched into fringe. Rough-times tattoo's what dogs called the injuries they survived when they roamed alone and without a pack. The salty water triggered memories of those times. A small moan threatened to escape from his proud chest; he willed it down.

Temptations--rotten crab meat and limu-- were hard to resist, but the dog knew they had only a little time before sunrise, and the run down the beach had been fun. 'Next time,' thought Grog.

Samuel at four could sort smell because he was trained to know the difference between something that was not quite right, and something that was way the hell wrong.

"Don't go telling your mother I told you that." His grandmother was joking, mostly. "She worries I'll turn you hyper-sensitive and ..." Her thoughts trailed. Samuel picked up the dropped words.

"Don't tell Mom, you taught me to know that smell." Samuel pointed in the direction of the neighbor's dryer, and finished... "that smell, is way the hell wrong." They both knew it was the 'way the hell' part that wrinkled his mother's otherwise flawless smooth face. The two friends giggled at the thought, and shot a wink to seal the secret. The wink shimmied mid-flow turning to stardust. Samuel could not be sure things like that happened to other boys his age. "It makes no never mind, honey," his Tutu read his mind as a matter of nature, like knowing the tides.

Samuel's grandmother -- his Tutu -- was his most favorite person. A person he wished would be with him every day, all the time. While she was with him, Samuel and his Tutu had great moments. Samuel, like most young children had a broad mind -- he was curious about everything --and had even broader heart. He had lots of room for people he loved. He also paid attention. The strange floating feeling rippled through him; tossed his heart.

He missed his Tutu. Samuel felt his heart squeeze in his chest thinking about her. He reached for his baby finger, something his grandmother had taught him. "Just a gentle jump," she'd say to him. "Anytime. Anywhere." A couple minutes was all it took for Samuel's heart to release the ache. He could almost hear his grandmother assuring him with her laughing eyes magnified in the old round wire framed glasses. He could hear her, "I'll be back." Of course she'd be back!

The smell of fresh-baked bread got stronger. The loaves were out of the oven. Samuel at almost twelve (his birthday was coming up) knew his dad would like it if he was there for breakfast, his mom would be getting the van ready for market, the twins were probably covered with more flour than was in the big rounds of bread scored with swirls and slit like ripe mangoes; and the baby would be wanting more milk.

It was farmers' market day, whatever bread his dad baked today would sell by the slice with a special blend of 'butter': a spoon full of liliko'i jam unsweetened, a pinch of spice -- sometimes chili powder, other times a pinch of black pepper, or black sesame seeds and finally 'swimming' herbs snipped weeks ago and packed in honey. That magical mouth-watering blend was a family secret: the exact proportions varied depending upon the ingredients. But what mattered most was how Samuel's Butter (for it was his nose that metered what was just right) led to the full spread of the family business: The Safety Pin Cafe Spoon, Spice & Herb Shop.

"Dad's baking rosemary and ulu sour dough. I hope he made extra. Extra ulu." Samuel reached for the soft spot behind the dog's ears, and scratched. Grog let out a long low sound somewhere between a groan and a bark. Ulu was his favorite food of all time. Samuel loved the sweet baked breadfruit too.

The small but sturdy pack sewn from bright highly visible nylon held Grog's leash and the lightweight scooter Samuel's father built from aluminum scraps, two steel conduits, and old tracks (skate board wheels). Black electrical tape trimmed with orange high visibility tape on either end of the shorter of the two conduits made holding on easier. Samuel pulled the folded scooter from his pack, tugged on the two hinges until he heard that click and lock, extending the riding surface to its 18 inch length. A battery operated light welded to the neck of the scooter automatic switched on when Samuel gripped the handle bars. His father was practical, and safety-first kind of guy. The light was 'old-school' not lithium. Two double AA-batteries in a thin case made it work.

The soft leather leash snapped easily into the ring in Grog's collar. Short legs and a belly just barely above ground, Grog had a powerful thick neck and shoulder muscles and thighs like a sumo wrestler. Smiling and serious (a necessary combination for adventure), stubby tail wagging, Grog flexed shoulders and backbone, and recalibrated for Samuel's additional weight.

Samuel wound the other end of the leash over the handle bars. "Ready for some breakfast?" The boy asked. The dog did not have to be asked a second time. Samuel adjusted the pack so he'd be visible in the early morning light. Grog gave Samuel a steely look, "You ready?" Samuel nodded and the race for ulu was on.

Just as he suspected, the van doors were open. Grog skid to a stop before hitting it, Samuel braced himself using his left foot for brakes on the grass that was still wet from kehau. The morning dew a sure signal it was going to be a hot day! The chocolate colored van with bright purple letters flowed on both sides of the delivery truck. The Safety Pin Cafe... spilled over the side where the doors opened to neatly stacked shelves. Spoon, Spice & Herb Shop covered the passenger-side of the specially designed van.

Samuel's mother, was just finishing up. Seeing dog and boy still wind blown from their adventure, and Grog's paws and belly covered with evidence of wet beach Mamo Black closed the delivery truck door, turned with that look of wonder that would not dilute. She didn't play favorites with her four children. But it was hard not to love Samuel without overflowing. He mea iki. It was a small thing ... to love him so. It took no effort at all.

Grog waited for Samuel to unleash him then rubbed up against Mamo. Mamo was Grog's most favorite person. They had grown up together, rescued together. She pulled her gloves off once the bread was stowed and crouched to hold Grog's face. 'My pack,' she crooned. 'You did good pal.' The girl who was now a grown woman with children was the only one who could turn him to soup.

Water. Grog needed a lot of it, and where was that promised extra ulu?

"Farmers' markets are a great place to collect gossip. Even with everyone masked and distanced, you can't hide your soul," Mamo Black carried the youngest of her children in a bundle wrapped up and around her shoulders tied in a knot below her belly. She was talking to the twins Kepa and Kalei who loved eavesdropping. Agile and fluid, the two did not look at all alike. Kalei was an ink black haired, kukui nut brown-eyed boy, and his twin had hair like molten Pele and eyes like lightning.

"Why would a person want to hide their soul Mama? Is it something to keep secret?" Kepa could no more keep a secret than stop breathing, unless she was diving. Then, it was a matter of testing and she was known to go for ninety seconds before surfacing.

"Honey, people, adults mostly, forget the connections we make ... with everything," the baby was squirming and wanted to eat. The table of baked goodies was nearly full with rounds of sour dough breads, long thin baquettes, and nets filled with fist-sized steamed buns. "You and Kalei can set-up camp under the table while I feed Nani. Don't get too niele, yet. People are just getting used to being in big crowds again. So, tune it down." She made a gesture with her right-hand dialing down her ear.

"Got you Mama." That's the thing about Samuel's family he loved best. The things that were important to his Mama and Dad weren't easily 'seen' but felt. So to talk about the soul and masks in the same breath made sense to the Blacks. In the everyday everyday, 'school' was everywhere.

Samuel was in charge of sales. He was good at math, but even better at selling. Though the big temple bell that was used to signal the start of every Wednesday afternoon market had not yet GONGED, people were circling, sighting the freshest looking fruit, the greenest leaves of bok choy, the most generous bags of poi and the best prices. The regulars knew him, many called him Kamuela.

"Eh, da bread smells ono." That was one of his neighbors, Mr. Santos. "I smelled um this morning but had to wait. So this better be good," He winked and Samuel knew the old man would buy a bag of the buns shaped like manapua, and two rounds of the rosemary and ulu bread. "Your regular, Uncle?" Samuel was already filling the denim bag, and had his bread knife ready to slice a thick hunk to toast and butter for the small brown man shaped like a tea pot.

"You got my numba, Kamuela. Your daddy coming today?" While the smell of rosemary and ulu filled the stall and beckoned along the airways above the Windward Marketplace, Samuel nodded. "Later but. He had to work." Samuel fingers mimicked being at a keyboard.

"They cannot let him go, right?"

Mamo Black chimed in, now the baby was fast asleep satisfied and full. "Part-time part-time is stretching to the end of the year."

"Then we can have our full-time baker and you folks gonna move to the new shop?" It was hard to keep secrets in the small town Mamo had known all her life. She reckoned her words, thinking about the complications and expenses involved with a new shop.

"Fingers crossed, Uncle." That was safe and not a lie. There was nothing wrong with crossing your fingers and asking for help with a dream still catching stardust and fertile dirt.

"Okay." Jeffery Santos nodded, letting the subject ride for now. "Whew, that bread smells delicious!" The toasted slice was just hot, very lightly brown and ready for a of spread Samuel's Butter, a mix that included black sesame seeds today.

"On the house, Mr. Santos!" Kepa shouted from the curtain tent. The man laughed at the formality remembering that so many of his former students at the community college would tease him with the "Mr." thing when he got too serious about formulas and chemistry. Kepa -- a grandmother in a kid's skin --never stopped amazing Jeffery Santos. Kepa knew their neighbor was the best of customers and also knew Mr. Santos had a big family who loved bread! Where Samuel had a nose for sorting smells, it was Kepa who heard everything. The GONG sounded just as Kepa crawled from the muslin table curtains dyed in the big rusty enamel pot in the Black's backyard. A muted yellow from freshly ground olena, turmeric stamped with a pattern of ash-colored triangles decorated the hem. Customers had begun to line up in front of the Safety Pin Cafe's corner stall.

"Wash your hands Kepa," Mamo Black kept two thermoses filled with very hot water for washing hands and a dispenser of unscented coconut oil soap. The twins were the kokua, the helpers who bagged breads and toasted the thick sour dough slices. Rubber gloves small enough for the young hands were necessary at this stage of virus on the brain times. Kepa pulled a pair onto her washed and dried hands. Everybody had their masks in place.

"Uncle," the girl said handing her neighbor the slice, larger than his palm. "Heard you folks going have a big pa'ina for graduation. Don't forget the baquettes." Kepa flashed a smile that could toast a dozen slices without thinking. Her mother was busy talking with customers, answering questions about the breads, taking orders and multi-tasking while never missing a beat. "Kepa," she shot the ehu-haired one a look that reminded her about the nosey-niele thing, and mouthed "Tune it down." But she knew Kepa wouldn't, couldn't and really ... who would want to squash all that light!

Setting up camp under the table was really code for stashing the latest variety of bread Samuel and Company (the tag everyone used to describe the Black Kids) stored for the final hour of market sales. It was a quirky idea the whole family had come up with.

"In case some customers, like you Dad, cannot come early to the market. Why don't we put some bread out last minute?" That was Samuel's thought.

"But the regulars who come early? What about them?" Kalei, born a full five minutes earlier than his sister liked being early.

"I like the idea of rescue me ... the two jobs and more daddy types," the baker was listening to all the chatter about market and bread. But mostly he loved hearing how his kids paid attention to the people who were their neighbors and other folks who they knew as customers.

"Yea," Kepa said. "You rescue me, I rescue you."

So on that Wednesday market day, the bundle of bread surprises were "Last minute bagels." The child-sized experimental batch of four dozen lumps of dough with puka, holes, in them sold for $1 a piece or three for $2.50. A jar of Sam's Butter to go along cost $4.00 for a half-pint. The combo was a great package, a five dollar bill spent well, and gave customers a taste of the Safety Pin Cafe's signature sense of "a spoonful of spice and herbs at a safety pin price."

Samuel felt his fingers itch and his heart twitched. It was his Tutu ... checking in. The pricing on the bagels was Samuel's idea though hisTutu did make a suggestion: "Make enough to share and enough money to make one more. My Tutu would have told me that one, Samuel." He set the "Last minute bagels" out in a calabash lined with two big napkins made from the same 'olena dyed muslin as their camp curtains. He stopped for a couple minutes freeing his hands up and pressed his thumbs onto the moons of his ring fingers. "To flow Tutu."

⚡

Sam and Iliahi stood in the ocean faces still tattooed with sleep. Sam wore a stocking cap tugged over his ears and the saggy old brown hoodie that was his tutu's. The morning was always cool before sunrise. The smell of rose water lingered in the cotton fleece. He inhaled deep, burying his nose in the sleeve covering his right arm, blinking slowly to clear the sleep from his eyes, and the tears. The tears fell off his high cheek bones and joined the small waves that climbed his legs.

Iliahi had his goggles up over his forehead. His head and torso covered with a brand new camo hoodie. His hair was braided and hung down his back. Standing to wait for the sun, the boys let the cold ocean recalibrate their bodies' temperature.

"Whoa, feels kinda cold today. Taking me long time to get ma'a," Iliahi closed his mouth to keep his teeth from chattering. Sam just nodded, silence was easier for him plus Grog leaned into him so close it was like wearing an old wet rug.

Grog was immune to cold. His black coat was thinning but he was a beach dog, born raised and tempered by the ocean. His first home. He looked for the okay from Sam his short legs paddling to keep close as he waited to be unleashed and with a swift sweet ruffle to his head, Grog was unhooked reaching for the sandy shore, then sprinted like a pup.

Sunrise on the windward side was exactly like pulling the huge ball of fire up and out of the ocean with throw net. Well, that was the way the boys talked about their morning ritual. But, in the bigger picture they both knew they were welcoming Ka la, the Sun, and it was the chanting that would do that.

Iliahi's Aunty P. short for Pualani (only Iliahi could get away with calling her "Aunty P.") taught him the chant E Ala E when he was four. Mamo Black did the same with Sam, at the same age. "To welcome the sun you make connection with the sun outside, and the sun inside you. Sun outside. Sun inside. Same same. The heat, the light when Ka la comes and you oli him, you wake up, too." Aunty P. was twice the age of Sam's mother and had been her grandfather's side-kick for many years. Aunty P. was mother to an even dozen. Newly-toddling keiki (two of them at the moment), three almost teens (among them Iliahi), four high schoolers (including twins originally from Seattle) and two young adults who made the twins but weren't strong, healthy or willing to parent.

Pualani Sing's beach house was built in the '50's by her parents Mabel and Kekoa Sing. They were musicians and cooks; both of them did both activities equally well, but it was Mabel who had the touch and her family's recipe for Portuguese sweet bread. The kitchen was built like a well-kitted restaurant. The oven was both gas-powered and ingeniously created to be a wood stoked outside oven for the bread. A single story redwood home with three big bedrooms, bunk-beds in two rooms, two bathrooms inside, an outdoor shower and a wraparound lanai screened and louvered to be extra bedrooms for all comers. The living room was airy and divided from the kitchen by a half-wall making it easy to move food between the two main rooms. An old stand-up piano lovingly tended and tuned for decades held up the wall to Pualani's bedroom. When she was not at the keys, and someone else was Aunty P. loved to feel the vibration of the chords against the strung metal. It didn't matter what music. A stand-up bass held in stand and covered with a fine-mesh breathable cover of deepest almost navy blue was silk-screened in swirls of wind and ao, clouds like smoke. The two, piano and base -- guardians -- to those who slept. Lauhala mats, woven by Aunty P and her gang of weavers covered every floor except for the bathrooms.

Iliahi was a child made for the ocean, and the ocean cared for him. The hour before sunrise was his special time to be with the salty womb of all memories. With Sam, Grog and his goggles, fins and net bag Iliahi was fully at home. The first glow of orange began to puka over the horizon. No clouds to hide the dawn, but streaks of feathery wings of the manu absorbed the light to come. The boys clapped, and began to oli.*

The two boys repeated the oli until Ka la, the sun was fully awake and visible above the horizon. The pace was quick, upbeat, invigorating. There was really nothing like it!

"Whoa, he is big, and look," Sam pointed after a few silent moments. The sound of the oli reached across the top of the morning's ocean just as the brilliance of Ka la reached across the ocean's skin to oli back to the boys.

Bam! Ignition! The two friends hand slapped and hip bumped their signature sunrise moves and Iliahi walked out of the water to pull his hoodie off, and reach for his net bag from the sweatshirt pocket. Short diver's fins dangled off a twist of purple bandana around his neck. The bandana went into the pocket of his nylon shorts, at the water's edge Iliahi pulled the fins onto his feet. He spit into the glass of his goggles and rubbed. The goggles were old, but well-tended. They were wood, and real glass, not plastic so they were heavier than masks sold today.

Making the sign of the cross and asking for protection from Mary, Iliahi waded in and stroked. Sometimes he would gather limu, seaweed or he'e if it was the right moon. He didn't usually use a spear to fish. "No need," was all he'd say if someone asked. But. Mostly people never ask if you going fishing. No need be niele. There was a protocol.

Sam watched as Iliahi swam out to the reef and waited to see that the small bright inflatable orange float marked his spot. He would spend his sunrise swimming within sight of the float, backstroking each way, making it easy to keep an eye out for his friend. "Never dive alone." First rule. Iliahi did not like having someone too close. Sam was a strong swimmer and more than that a loyal friend, though he was that. He could feel Iliahi.

E Ala E. Welcome the Sun. And yes, Ka la welcomed the boys.

⚡

A sharp whistle caught Samuel's attention. "E, Imagination. You saved some for me ... right?" It was Iliahi, and he was not alone.

Sam's phone vibrated and chirped at exactly the same time as Iliahi's whistle cut across the distance of two vendor's stalls. The chirp -- Song Sparrows -- was his tutu's ring. She'd recorded the Song Sparrows in the woods where she lived. Sam turned it into "Tutu's Ring" on his phone. She was sending him a text, with pictures. The two thousand mile separation between this boy and his grandmother was a heart-skipping distance. Never seen, but never not felt.

⚡

⚡

Samuel loved the smell of bread. But even more than that, he loved the smell of the wheat berries when his dad milled the hard kernels. His was a sensitive nose, and even before a loaf of Emmer and Bauermeister wheat was baked and pulled from the racks, Samuel knew.

"I smell chocolate mister!" It was his way of i. d.ing the bread made from hard red winter wheat that smelled like chocolate. His dad was one of the small artisan bakers inspired by stories in a book called The Third Plate written by Dan Barber. Was it possible to love taste because you heard about it?

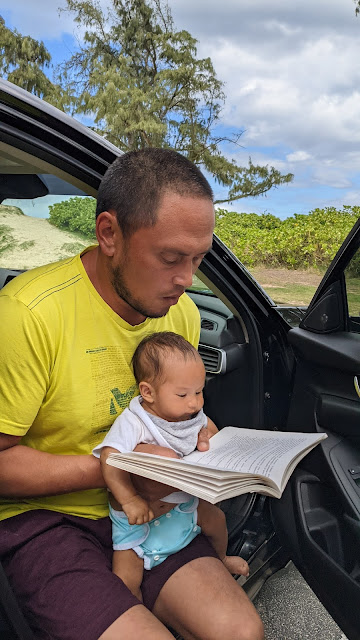

|

| A son reads to a son ... real-time |

That question among all the other elemental factors settling into place had led to this moment. "Isn't that exactly what every living being has always done? Listen to the sound our mothers, or fathers 'told' us were the good stuff to eat, the best things to eat and the things to avoid." Pualani Sing waited for Samuel's dad behind the wheel of her Candy Apple Red Ford 250 pickup. Mamo and Pua bounced the energy of the evening adventure between them in the large cab. Two of the kupuna from Weeders Ho'i volunteered to set up overnight campground in the Sing's backyard. Samuel's dad finished unloading bags of bagels, granola and loaves of sour dough breads.

"We won't be long, and anyway, you can always call for back-up," the silver-haired goddess blew a kiss to her friends. Any and all of the crew wouldn't think of turning down a call to help out. On this particular night, Clarence and Alma Pang were part of the back-up. Pre-arranged by the goddess herself.

"Hope we can keep up with them, Clarence," Alma giggled. The tiny woman was nearly eighty but was smart thinking and agile with her movements. Dressed in a lined yellow and black plaid flannel jacket and black cotton tights, Alma Pang carried a bright blue nylon backpack filled with small gourds.

"Some of the kids might like making flutes, or rattles. You never know."

Clarence was nearly deaf, even with hearing aids but his sense of humor had always been quiet and since words were never his first priority it suit him to simply read her lips and nod. Love was big between these two old dears and that went a long way.

"Sure wish Kaulana could've been here to see this." Clarence's near-whispering voice was loud enough for the two boys who always managed to stay within six to ten feet of him.

Iliahi had his hands full of hand tools, but he caught Samuel's eye and let out a soft whistle. "What?" Samuel said without talking. They'd heard what they heard and knew there was only one Kaulana. The shadows had all but disappeared, and the garden lights flicked on along the lanai. One lantern in the mango tree, carved from a large ipu gourd Alma and Clarence grew dangled like an opu after a good meal letting pin-pricked light through to mimic Makali'i. It had been Kaulana's favorite. "Looks like home to me," he'd say when life was getting little too heavy for his shoulders.

It wasn't often Mamo Black and her husband had a night off. This one was totally unexpected, not exactly a date but there was a feel of glitz in the night air. Mamo stretched her legs out in the jump seat of the pickup. In the moments of silence she remembered when her grandfather made room for a small black pup he'd found. Wandering on the beach not far from Pua's beach house with no more than his ribs and four big paws to hold him together, her grandfather simply named him "Grog" because the mutt was groggy on his feet. "We keep him. Feed him good stuff, and this truck? This truck will be his home. This guy is used to roaming."

Samuel's dad climbed into the passenger seat, reached across the console and gave Pua honi. Even in the dark the sunglasses were in place. Foreheads together, he breathed in the smell of her sandalwood self. It had always been sandalwood equal Aunty Pua. "So Aunty," Samuel's father began. "You're up to something. And I figure it is some kind of big picture operation."

Pualani Sing laughed. "You got that right. Somethings ripen fast, like hot house tomatoes. Geez, do people even call hot houses hot houses?"

"Hoop houses. Or green houses mostly," Mamo suggested. "But really in Hawaii, it's not so important to have hot house, as it is important to try to keep plants from getting too hot."

Pua nodded, and then continued with her original train of thought. "Not every plant, or idea get ripe fast. Sometimes it can take forever, to see something get mele. Samuel's Father, we are on our way to a melemele time and place."

It was a short ride to the old corner hardware store. The building had been vacant for sometime, but the mana of protection was strong and no one messed with this kind of magic. Pua pulled the red pickup into the alley and kept the headlights on. "Honey girl, you and your kane climb out and hemo the lock on the back door." She reached into the glove box and handed Samuel's Father the keys. "The light switches are inside the door on the wall to the right. I'll wait here." The two riders looked at each other for a heartbeat, maybe two or three.

"Go. Go. It's cool. Really," Pua's long powerful fingers flicked the air like she was sprinkling holy water.

The lock was thick metal. They'd find out later, it was titanium. Of the two keys in his hand, Samuel's Father chose the larger. It slipped in as if it had been there the night before. "Neva under-estimate a good lock and even more neva under-estimate knowing a good locksmith."

"Did you say something, Mamo?"

"No, wasn't me. But I heard it. The thing about a lock and a locksmith. Sure sounded like Pop." Samuel's Father had never met Kaulana Black but the hair standing straight up on his arms were pretty darn sure Pua had pulled all stops out of her magic.

The lock held the original barn door in place at the back end of the building. Sliding smoothly, again as if someone had oiled and kept the tracks in good order, Mamo pushed the door open. Samuel's Father reached for the light switch, it was a dial so he pushed it. Set to a very low setting the bank of recessed lights along the ceiling mimicked the constellation of the Pleiades, Maka'lii.

"Feels like home to me."

"Okay Pop, that's you right? This is all about you and your tricks. Sleight of hand, and out of mind. You disappeared and now you're back. Kinda. Sorta."

"Look around Honey Girl. Remember what Pua said, 'sometimes it takes forever for something to come mele."

Two full-sized gas ovens, marble counters, and rolling racks with trays that like the lock and door looked as if they were cleaned and readied the night before.

"I remember Pop's Hardware from when I was a kid. This backroom was where Uncle Clarence would sharpen tools and teach my grampa how to repair the tools. There was a small stove and oven for cooking, and a closet door that dropped down with a bed behind ...

"For when we got too tired to drive home. Hooks from the ceiling held a hammock. Look up, Honey Girl." The large heavy-duty stainless hooks dangled from two lengths of chain above their heads.

"Some things change. Some things stay the same." Samuel's Father remembered that his mother had always said that. But only after he became a father did that make as much sense as it did now.

Samuel's Father had a smile that could pop corks on champagne bottles if and when he wanted to. But that smile was reserved for special occasions. This was one of them!

"Find the something that fits that other key."

It didn't take much for Mamo to follow the 'map' Pop had left for her. When she turned the dial on the light to full illumination she had a good look around. The commercial size ovens were real. At least tonight they were real. But, it was when she turned the lights nearly off, and the room was almost dark when she saw the luminous drawing of an ipu in the shape of an opu after a good meal. Painted into the ceiling the stars of Makali'i poured into a palm-sized shovel held in place over peg-board at the far corner abutting the back wall. When Mamo lifted the shovel off, the peg-board came with it. Behind it was a door, nearly invisible unless you knew to look for it as if it didn't matter.

This lock was no larger than the nail of Mamo's pinkie finger. "Go." Samuel's Father slowly undid the smaller key from the woven rope and gently tucked it into Mamo's right palm. Before trying it in the tiny keyhole Mamo pulled on the long silver chain she always wore round her neck. A silver apple locket dangled from the chain. The hoop for the key was much the same as the one at the top of the locket, she slipped the key onto the chain like a charm.

"Feels like good lucky to me," she said almost too quietly to believe it. 'Good lucky' was what her grampa said when he was feeling that sweet kiss of turning fortune.

"It's the ripest kind of luck. Push, Honey Girl." When the key turned smoothly to the right her Pop's voice was clear but fading. Mamo knew her grampa wasn't staying. She thought of Grog, and before thinking she asked, "Will you be taking Grog?" There was no answer. When she pushed on the door in the wall it sprung open with no squeaks or rattle. Inside was a simple heavy envelope with faded red ink written in capitals "FOR MAMO, MY DAUGHTER. WHEN THE TIME IS RIPE."

Tents, and blankets hung over the clotheslines held in place with paving stones normally lining the herb garden, overflowed with keiki of all sizes. Sleeping bags and pillows spread across the yard. Four lounge chairs stretched out strategically. Intended for the volunteers, small fries clambered on the chairs like seesaws while Clarence, Alma and four of the regular weeding gang sat cross-legged on the grass surrounded by children with screw drivers, felt-tipped markers and gourds long, squat, oblong and in different stages of becoming musical instruments.

Pua parked behind the cars and trucks in her driveway, turned the headlights off. She let out a deep breath that left old but, water logged with tears and time. The goddess took her sunglasses off, tucked them up into her thick silver hair, crossed her backyard found one of the empty lounge chairs and parked herself. Iliahi saw her first, and without asking filled a tall glass with lili'ko'i lemon aide. "Thank you Ahi. Any chance there's still some Old 100 left?" The flagship bread was still her favorite with a nice layer of Samuel's Butter with black sesame seeds.

Samuel was busy helping Clarence with the puka, holes, for the gourds that would be nose flutes but he noticed his mom and dad weren't with Pua. Clarence heard a car pull onto the gravel driveway. Samuel heard it too, but knew it wasn't the van or his dad's truck. Instead, a man the size and shape of a tea-pot walked across the backyard. "E Uncle," Sam said. It was his neighbor Jefferey Santos.

"E Kamuela. Nice night." Jefferey Santos lifted his head in the direction of his old friend and college-pal. Clarence motioned to his wife, now completely surrounded with the sounds of nose flutes.

Kamuela noticed the dirty apron and gloves hanging from his neighbor's back-pocket. Not usually so inquisitive, the boy felt his chest swell with an urge to know. "You been busy," he said, hoping for some elaboration.

"Not too busy, and not far away. Just taking care of something that was ripe." Even over the sounds of palm-sized ipus blowing into the night, Alma Chang heard the collaboration of Time.

Samuel felt his fingers tingle. Setting the screw driver down he wondered out loud, "Where's Grog? He was snoring under that lawn chair all night."

"I think," Clarence paused a long moment, "Grog has a date." A tender softness spread across the old man's face. An ageless expression.

Samuel considered the idea then said it like he meant it, "He always did like to roam."

*The oli E ala e was written by Pualani Kanaka'ole Kanahele in 1993 for the ceremony returning Kanaloa (Kahoolawe) to the people. This is an oli specifically chanted at sunrise.

Comments

Post a Comment